In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Introduction to Ghee 2. Definition of Ghee 3. Statistics of Production and Consumption 4. Physico-Chemical Constants 5. Food and Nutritive Value 6. Market Quality 7. Keeping Quality 8. Renovation 9. Neutralizing High-Acid Ghee 10. Marketing 11. Problems of Adulteration 12. Grading-Agmarking 13. Judging and Grading 14. Uses.

Contents:

- Introduction to Ghee

- Definition of Ghee D

- Statistics of Production and Consumption of Ghee

- Physico-Chemical Constants in Ghee

- Food and Nutritive Value of Ghee

- Market Quality of Ghee

- Keeping Quality of Ghee

- Renovation of Ghee

- Neutralizing High-Acid Ghee

- Marketing of Ghee

- Problems of Adulteration in Ghee

- Grading-Agmarking of Ghee

- Judging and Grading of Ghee

- Uses of Ghee

Introduction to Ghee:

Beginning from almost Vedic times (3000 to 2000 B.C.), there is ample recorded evidence to show that makkhan and ghee were extensively used by the early inhabitants of India both in their dietary and religious practices.

Thus, the Rig-Veda (the oldest of the Vedas) contains the following translations of the Sanskrit passages:

(i) ‘Give us food of many kinds dripping with “butter” (i.e. makkhan).’

(ii) ‘The stream of “ghee” descended on fire like deer fleeing from hunger.’

(iii) ‘The streams of “ghee” fall copious and rapid as the water of a river.’

(b) It is worth noting that the utilization of milk fat in the form of ghee, so admirably suited to this country, should have been hit upon in such early times. This unique position occupied by ghee may be ascribed to its being not only the best form for the preservation of milk fat under a tropical climate, but to its constituting, in addition, the only source of animal fat in an otherwise predominantly vegetarian diet.

The large production of ghee is due to:

(i) Concentration of milk production in rural areas which are far away from the nearest urban consuming centres;

(ii) Lack of all-weather and refrigerated transport facilities;

(iii) Unfavourable climatic conditions, i.e., high temperature and humidity, for most parts of the year, causing rapid spoilage of milk;

(iv) Its long keeping quality under tropical storage conditions and ordinary packing;

(v) Market demand. (It is the only source of animal fat in the otherwise predominantly vegetarian diet of most Indians.)

Definition of Ghee:

Ghee may be defined as clarified butter fat prepared chiefly from cow or buffalo milk. (Sheep or goat milk is also employed, although rarely, in the preparation of special- designated ghee.)

Note:

To clarify means ‘to make clear’ a liquid or something liquefied, by removing unwanted solid matter or impurities.

According to the PFA Rules (1976), ghee is the pure clarified fat derived solely from milk or from desi (cooking) butter or from cream to which no colouring matter is added. The standard of quality of ghee produced in a State or Union Territory specified in column 2 of Table 11.24 should be as specified against the said State or Union Territory in the corresponding columns 3, 4, 5 and 6 of the said Table.

Explanation:

‘Cotton tract’ refers to the areas in the States where cotton seeds are extensively fed to the cattle and so notified by the State Government concerned.

Statistics of Production and Consumption of Ghee:

The production of ghee in India in 1966 was estimated to be about 32.7 per cent of the total milk production and 58.9 per cent of the milk used for the manufacture of dairy products. Today, the total annual ghee production may be estimated at over 500 million kg. with a value of Rs. 1.250 crores at the present rates.

The percentage conversion of milk into ghee varies from State to State. The largest ghee-producing States are- Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Punjab, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Haryana etc. Buffalo milk is preferred for the manufacture of ghee because, being richer in fat content than other types of milk, it gives a larger yield of ghee. The production of ghee is higher in winter and lower in summer corresponding to months of higher and lower milk production. The bulk of the ghee sold in the market is mixed (cow and buffalo).

Of the total production, on an average, less than one-fifth is retained by the producers for their own use, and the remainder is released for market sale. However, this proportion varies from place to place depending upon the status of the producer, his financial standing, dietary habits, proximity to the market, approaching festivals, season, etc.

The demand for ghee is mainly concentrated in the urban areas. The per capita consumption largely depends on the market price and availability of ghee substitutes, family income and habits, etc. The average per capita consumption of ghee today works out to less than 1 kg. per annum for the whole country.

Composition:

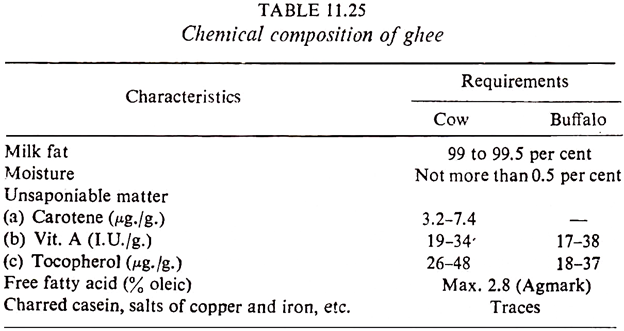

The general chemical composition of ghee is shown in Table 11.25.

Physico-Chemical Constants in Ghee:

Ghee, as in the case of other fats and oils, is characterized by certain physico-chemical properties, which have been found to be the basis for the fixation of certain physico-chemical constants for defining the chemical quality of the product.

These properties, however, show some natural variations depending on such factors as- method of manufacture, age and condition of the sample, species, breed, individuality and the animal’s stage of lactation, the season of the year, region of the country, feed of the animal etc.

Some of the important analytical constants or standards of mixed ghee produced under standard conditions are given below:

(i) Melting and Solidifying Points:

The melting point varies from 28°C to 44°C, while the solidifying point varies from 28°C to 15°C. (Being a mixture of glycerides, ghee does not have sharp melting or solidifying points.)

(ii) Specific Gravity:

This varies from 0.93 to 0.94.

(iii) Refractive Index:

The Butyro-Refractometer (B.R.) reading (at 40°C) varies from 40 to 45.

(iv) Reichert-Meissl (RM) Value (also known as Reichert Value):

This should normally be not less than 28 (except for ghee from cotton-seed feeding areas, where the limit is 20).

(v) Polenske (P) Value:

This should normally be not more than 2 (except for cotton-seed feeding areas, where the limit is 1.5).

(vi) Saponification Value:

This should normally be not less than 220.

(vii) Iodine Value:

This should normally vary from 26 to 38.

Note:

The above ‘standards’ are all determined under standard analytical conditions.

Food and Nutritive Value of Ghee:

Ghee is the richest source of milk fat of all Indian dairy products. When prepared by the traditional country method, it is normally very low in fat-soluble vitamins A and D, and contains an appreciable quantity of these only under certain prescribed conditions.

(The losses of these nutrients from ghee during handling, storage and cooking; ghee as a source of nutrient in the Indian diet; the digestibility and absorption of ghee in the human system; the superiority of ghee as a food fat; ghee in the diet and Atherosclerosis—all these and other aspects of the food and nutritive value of ghee have been the subjects of early investigation by various research-workers).

Market Quality of Ghee:

This refers to the physico-chemical properties of ghee offered for sale in the market. The physical properties include colour and flavour (smell and taste) and texture (grain and consistency), while the chemical properties include chemical composition, etc.

The physico-chemical constants are also included under market quality. The quality of ghee is dependent on the type of milk (viz. cow, buffalo or mixed) feed of the animal, season and region, and the method by which it is produced (viz., desi, creamery-butter or direct-cream method).

(a) Physical Quality:

(i) Colour:

The colour of ghee manufactured from either cow or buffalo milks is definitely influenced by the method of production. The colour of cow ghee by the desi method is deep yellow, while that of buffalo ghee is white with a characteristic yellowish or greenish tinge. When prepared by the creamery-butter method, the colour of the product is similar to that resulting from the desi method, although of a somewhat lower intensity.

By the direct-cream method, the colour of cow ghee is again deep yellow, but that of buffalo ghee is waxy-white. Ghee from mixed milk (cow and buffalo) has a shade of colour proportional to the components of the mixture. The colour of ghee also depends on whether it is in the solid or liquid state.

(ii) Flavour (Smell and Taste):

This is the most important characteristic looked for in ghee by the trade. The smell is ascertained by rubbing a small quantity of the sample briskly on the back of the palm and inhaling it. Normally, a well-prepared sample of ghee has a pleasant, cooked and rich flavour. The taste is usually sweet and characteristic of the milk fat, although a slight acidic flavour is preferred.

Note:

Numerous publications have appeared in the country during the last decade on the means of identifying the flavour of ghee, for which research journals may be consulted.

(iii) Texture (Grain and Consistency):

Grains of a large and uniform size, and a firm and non-greasy consistency, are preferred. The grain-size in ghee depends mainly on the following factors- rate of cooling; fatty acid make-up (which is influenced by species of animal, nature of feed, season and region etc.), and subsequent heating and cooling treatment.

Yield of Ghee:

(a) The yield of ghee from milk cream butter is influenced chiefly by:

(i) The Fat Content of the Raw Material Used for Ghee Making:

This is calculated by multiplying the amount of raw material used (viz., milk, cream or butter) by the fat percentage in the same. The higher the fat content, the higher should be the yield, and vice versa.

(ii) The Percentage of Fat Recovered in Ghee:

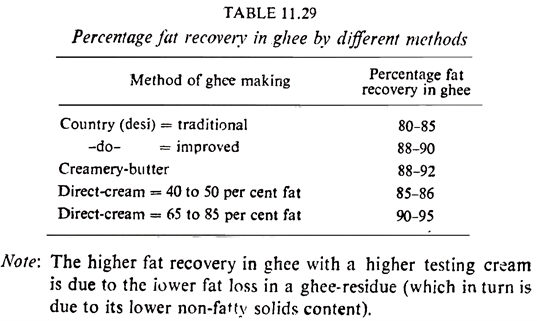

This depends on the method of manufacture (see Table 11.29).

(b) The items of fat loss in the different methods of ghee making, starting from milk, are given in Table 11.28.

(c) The approximate fat recovery in ghee by different methods, starting from milk, is shown in Table 11.29.

(d) The percentage fat recovery in ghee by three different methods is given in Table 11.30.

Note:

1. In an earlier work, the percentage fat recovery figures in ghee were reported to be 87, 93 and 86 for desi, creamery-butter and direct-cream methods, respectively.

2. The possibility of recovering a higher percentage of ghee from high-fat cream or washed-cream has also been reported.

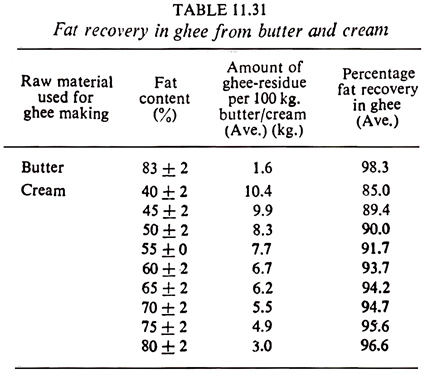

(e) Comparative study of fat recovery in ghee from butter, and creams of varying fat contents. This is presented in Table. 11.31.

Keeping Quality of Ghee:

(a) Unlike all other indigenous milk products, ghee has a remarkably long keeping quality. Under optimum conditions of production, packaging and storage (viz., when prepared either by the direct heating of sweet cream or sweet cream butter, packed up to the brim in a new rust-free container and stored under sealed conditions at around 21°C), ghee is expected to have a storage life of 6-12 months. The keeping quality of ghee is adversely affected by increase in acidity and development of fat off-flavours, viz. rancidity, oxidation, tallowiness, etc.

The factors influencing the keeping quality or shelf-life of ghee are:

(i) Temperature of Storage:

The higher the temperature of storage, the lower the keeping quality, and vice versa.

(ii) Initial Moisture Content:

The higher the initial moisture content, the lower the keeping quality and vice versa.

(iii) Initial Acidity Content:

The higher the initial acidity content, the lower the keeping quality, and vice versa.

(iv) Initial Sediment Content:

The higher the initial sediment content, the lower the keeping quality, and vice versa.

(v) Copper and Iron Content:

The higher the copper and iron contents, the lower the keeping quality, and vice versa. (Copper and iron content act as a catalytic agent in fat-oxidation.)

(vi) Method of Packaging:

The higher the air-content in the head-space in packaging, the lower the keeping quality, and vice versa.

(vii) Exposure to Light (Especially Sunlight):

The greater the exposure to light, the lower the keeping quality, and vice versa.

(b) Extending Keeping Quality:

The keeping quality of ghee can be extended by the addition of artificial anti-oxidants. Under the PFA Rules (1976), butylated hydroxy anisole in a concentration not exceeding 0.02 per cent is permitted at present. The action of anti-oxidants in prolonging the shelf-life of ghee is similar to that of butteroil.

Numerous studies were carried out nearly two decades ago on the preservative action of anti-oxidants, natural or artificial, on ghee. A few studies have been carried out in recent, years. It is claimed that ghee-residue acts as a good antioxidant when added to ghee—this may be due to its higher phospholipid content.

Alternatively, the phospholipids can be extracted from the ghee-residue (through a simple process of solvent extraction) and added at 0.1 per cent of ghee; such addition has been found to increase the keeping quality of ghee by two or three times as compared with that of untreated ghee.

(c) Accelerated Oxidation Test to Determine the Shelf-Life of Ghee:

There is yet no reliable test for measuring the developed rancidity and correlating the same with the keeping quality of ghee. Determination of the Induction Period (IP) for oxygen absorption at an elevated temperature of 79°C for ghee has been observed to be helpful in predicting its shelf-life. An Induction Period of 20 hours or more appears to correspond to a marketable life of 6 months.

Note:

The Induction Period is the period measured in hours, after which the rate of increase in the peroxide value of a ghee sample shoots up.

Renovation of Ghee:

This refers to the market practice of attempting to improve old and rancid ghee, so as to make it marketable as a product of secondary quality.

Some of the methods employed for the renovation of ghee include:

(i) Re-heating inferior ghee with curd, betel or curry leaves, etc., and subsequently filtering it;

(ii) Adding a yellow substance, such as saffron, annatto, turmeric juice, etc., to make it appear that it is cow ghee;

(iii) Blending an inferior ghee with a superior quality product.

Note:

The above practices are generally carried out in a crude manner.

Neutralizing High-Acid Ghee:

Market ghee sometime, develops large quantities of free fatty acid (predominantly oleic), which result from faulty methods of preparation and storage. This high-acid ghee produces harmful effects in the body system. The problem was tackled nearly three decades ago when two processes of neutralization were developed. In one, the neutralizer used was sodium hydroxide, while in the other it was lime.

The latter process, which is more suitable for small operators, is as follows- ghee which is to be refined, is heated to 60-70°C. Finely ground, good quality lime (preferably shell-lime), powdered to 60 mesh, is then sprinkled on the surface @ 3 per cent of ghee.

The temperature is quickly raised to 108°C with gentle stirring, and the mass is cooled and filtered at 60°C. By both the above neutralization treatments, the flavour, granularity and keeping quality of high-acid ghee are all improved.

Marketing of Ghee:

(a) At present there is no organized system for the production and marketing of ghee in India. Ghee is produced, by and large, on a small and scattered scale. It is assembled for marketing through middlemen. Adulteration at all stages of assemblage is a rule rather than an exception.

(b) The various agencies engaged in the assembling and distributions of ghee are:

(i) Producers;

(ii) Village merchants;

(iii) Itinerant traders;

(iv) Commission agents (Arhatyas) and wholesale merchants;

(v) Co-operative societies,

(vi) Retailers.

(c) The itinerant traders and brokers collect desi butter or kachcha ghee and make it over to wholesale merchants. The latter carry out what is known in the trade as the ‘refining’ of ghee. This process consists in mixing and blending different lots of makkhan/kachcha ghee in large karahis and then heating the mixture to a certain temperature in order to remove all traces of lassi.

This product is then transferred to settling tanks. The clear ghee is packed in tin-containers and stored in a cool place for a couple of days for proper crystallization or grain formation.

(d) At present, most ghee producers in India are financially dependent on unscrupulous money-lenders or wholesale merchants, who impose stringent conditions. Very often makkhan or kachcha ghee collectors make interest-free advances to the producers on the condition that the latter will sell to the former a specific quantity of ghee at a predetermined price, which has no relation to the prevailing market price.

Problems of Adulteration in Ghee:

(a) The adulteration of ghee in India today is indeed most appalling. Being the most expensive of the edible fats, ghee offers itself as easy prey to admixture with cheap adulterants by the numerous middlemen through whose hands it has necessarily to pass.

The natural variations in the analytical constants of ghee, make adulteration difficult to detect. Numerous studies were carried out two or three decades ago on the adulteration of ghee and its detection. A simple yet quick method for the detection of vegetable fats in ghee by a thin-layer chromatographic technique has been developed.

(b) The main adulterants of ghee are:

(i) Vanaspati (Hydrogenated Vegetable Oil):

This is by far the most widely used today, because of its close resemblance in texture, grain and colour and other characteristics of ghee.

(ii) Refined (De-Odourized) Vegetable Oils:

Examples are- groundnut, coconut, cottonseed oils, etc.

(iii) Animal Body Fats.

(iv) Miscellaneous:

The addition of minute quantities of rice, potatoes, plantain, etc., for improving the consistency of liquid ghee and inducing better grain formation has also been reported.

(c) Enquiries reveal that adulteration takes place at all stages of production, assemblage and marketing; however, the maximum adulteration takes place at the last stage. Although concerted attempts are being made by the government to insist on legal standards for market ghee, the lack of a well-organized system of food inspection, availability of laboratory facilities and easy methods for detection of adulteration have all contributed towards the continuance of adulteration in ghee on a wide scale.

(d) The Government of India has made it compulsory that all vanaspati must contain a maximum of 5 per cent of sesame oil, which can be identified in ghee by a simple colour test (known as the Baudouin Test). By means of this test, adulteration of ghee with vanaspati to an extent as low as 3 per cent can be detected.

However, the possibility remains that hydrogenated fats sold under different names for special purposes may still be used as adulterants. Further, since the legislation does not apply to refined oils, it has not been possible to completely eliminate the adulteration of ghee with such materials.

(e) Apart from the compulsory addition of sesame oil to vanaspati in order to facilitate its detection in adulterated samples of ghee, attempts had been simultaneously made to evolve a suitable colour for vanaspati, which will enable the consumer to detect the addition of vanaspati in ghee at first sight. The pink extract from the roots of rattanjot (onosma echioides), grown in some parts of Uttar Pradesh had been tried out nearly three decades ago for colouring vanaspati.

Extracts of turmeric and chlorophyll had also been suggested for producing an easy-to-detect colour in adulterated samples. But these attempts have not so far been wholly successful, as most vegetable colours which are acceptable to the vanaspati trade, can easily be bleached by simple treatment.

The problem is one of evolving a harmless dye with a pleasing colour acceptable to vanaspati manufacturers, which produces at the same time a permanent colour and is amenable to quick detection when present in small amounts in adulterated ghee samples. Food laboratories in the country have been engaged in these problems and it is hoped that a satisfactory colour will be evolved in due course of time.

Grading-Agmarking of Ghee:

Need for Grading:

The quality as well as purity of ghee can be judged only by detailed physical and chemical analysis. Contrary to general belief, it is not possible for an average customer to judge the purity of a sample of market ghee by its appearance, taste or smell, at the time of purchase.

Under existing trade practices, a limited effort to grade ghee for marketing takes place at different stages of its assembly, by thumb-rule methods. Grading, i.e. classification according to quality, assures the customer of quality and purity of the ghee and its need, therefore, is obvious.

The Agmark Ghee Grading Scheme:

Literally, Ag mark is an insignia—AG for ‘Agricultural’ and MARK for ‘marking’. With a view to developing the orderly marketing of agricultural produce on an all-India basis, the Indian legislature had passed the Agricultural Produce (Grading and Marking) Act, 1937. This Act, which is permissive in nature, provides for the grading of ghee on a voluntary basis.

The agmark ghee grading scheme was initiated by the Agricultural Marketing Department as early as 1938. Under the scheme, recognized ghee dealers (individuals, groups of individuals, cooperative organizations and similar bodies) can market ghee in standard containers bearing the seal of authority of Agmark, and designating the quality of the product.

Objectives:

The Agmark (ghee) grading scheme was introduced mainly to achieve the following objectives:

(i) To assure the consumer a produce of pre-tested quality and purity:

(ii) To enable manufacturers of a high-grade product to obtain better returns, and

(iii) To develop an orderly marketing of the commodities by eliminating malpractices when transferring them from the producer to the consumer.

(d) Prerequisites Jar Using the Agmark Label:

Grading under the Act is voluntary. Applications from interested parties for the issue of a certificate of authorization for the grading of ghee should be submitted on a prescribed form through the State Marketing Officer to the Agricultural Marketing Adviser to the Government of India. If on receipt of the application, the party is considered suitable, then the necessary permission is granted.

The bonafides of the ghee manufacturer or packer are determined by the following considerations- it is essential that while the ghee manufacturer should have the full facilities of a modern dairy factory for ghee-making and storing, the ghee packer should have a modern refinery and spacious godown; and both should have a well-equipped laboratory, a qualified ghee-chemist, etc.

The refinery of a ghee packer should consist of a heating furnace provided with a suitable chimney as an outlet for smoke, one or more heating pans, a settling pan or tank, and godowns where ghee tins can be kept in safe custody prior to analysis. There should be enough space for receiving butter or kachcha ghee and the testing of the same.

The ghee-testing laboratory should have precise equipment, apparatus, glassware and chemicals for the complete examination of ghee for its physico-chemical constants, free fatty acids, and performance of the baudouin test and phytosterol acetate test. The Agricultural Marketing Department provides all necessary assistance in the setting up and working of such a laboratory.

Procedure for Using Agmark Label:

The ghee manufacturer, who usually makes ghee from purchased milk or cream after thorough grading and testing, examines these records to certify the fitness of these raw materials for production of standard quality ghee.

For the ghee packer, the lot of raw ghee is examined for general characteristics and butyro-refractometer reading before purchase, and also examined for baudouin test and acid value. On passing the preliminary examinations, the same is heated at the refinery, usually to a temperature of 60-70°C, and the scum removed. Thereafter it is transferred to settling tanks and allowed to stand for a few hours so that the suspended impurities settle down.

A sample of each lot of freshly made ghee at both places (dairy factory and refinery) is drawn by the respective chemist and divided into 3 parts. One is analysed by the chemist himself. The other is sent for check analysis to one of the control laboratories maintained by the Agricultural Marketing Department. These are- the Central Control Laboratory, Kanpur (Uttar Pradesh) and the Subsidiary Control Laboratory, Rajkot (Gujarat). The third part is sealed and handed over to the packer for future reference.

After drawing the sample, the ghee is filled in new tins which have been previously marked with the following particulars- melt number, date of packing, place of packing, name of authorized packer, etc. If on analysis the melt satisfies the specification, the chemist arranges for the fixation of Agmark labels of the appropriate grade. All the above operations should be carried out under the supervision of the chemist. Ghee, filled in tins, should remain in the custody of the chemist till the labels are fixed on to them.

Agmark ghee is packed under two grades, viz. ‘Special’ and ‘General’, which are represented by two differently coloured labels. The only difference in the grades is in the maximum limit of free fatty acids (oleic), which in special grade (Red label) ghee is limited to 1.4 per cent and in general grade (Green label) to 2.5 per cent.

Agmark labels are printed under security conditions on watermark paper bearing the words ‘Government of India’ in micro-tint to avoid counterfeiting. These are affixed on the tins with a special adhesive supplied by the Agricultural Marketing Adviser to the Government of India.

Quality Control Checks:

If the Control Laboratory finds that a melt sample does not conform to the specifications, immediate intimation is sent to the authorized packer and the chemist to remove the Agmark label from all the tins filled from the melt in question, and the ghee rejected from Agmark grading.

A check on the quality and purity of ghee is also exercised by frequent inspection of the grading stations by the State and Central Marketing staff. Samples of graded ghee are collected from the grading centres and consuming markets (both retail and wholesale) through especially authorized officers. If, on analysis, a sample is found to be below specifications, the entire melt is declared misgraded and the packer has to arrange for the removal of the Agmark labels from the tins pertaining to that melt.

To ensure that graded ghee is not stored for an indefinite period so as to impair its quality, the chemists are also periodically required to draw representative check samples from stored tins of Agmark ghee and to send them for analysis to the Control Laboratories.

This ensures that the ghee contained therein has not developed an acidity in excess of the limit prescribed on the label. In the event of its exceeding this limit, it is downgraded from Special to General, or rejected, and the Agmark labels removed from the tins, as the case may be.

Agmark Ghee Specifications:

The original specifications introduced in 1938 have been modified and amended from time to time. It may be noted in passing that Agmark ghee can be freely marketed in any part of the country even though the Agmark specifications of ghee may differ from those prescribed by the constituent States of the Indian Union. The current specifications are shown in Table 11.32.

Progress of Agmarking Ghee:

Although the Agmark ghee grading scheme has been in operation since 1938, barely 2 per cent of the total ghee production of the country is handled today under this scheme.

The reasons for this slow progress are:

(i) Absence of quality consciousness on the part of producers and consumers;

(ii) Absence of standards for organoleptic quality in the product;

(iii) Difficulties experienced by Agmark packers in meeting all- India consumer acceptability due to natural variations in the quality of ghee produced in different regions of the country.

Judging and Grading of Ghee:

Score Card:

A tentative score card of ghee is given in Table 11.33.

Procedure of Examination:

(a) Sampling:

After thoroughly mixing the lot of ghee, obtain a representative sample with the help of a spoon.

(b) Sequence of Observations:

Note the sanitary conditions of the package/container on the outside; if there are any tin containers, also observe whether there is any rust. On opening the package, examine the ghee for its colour, texture (size of grains) and proportion of liquid fat. Then thoroughly stir the ghee and take a representative sample, and after melting it note the amount and nature of sediment.

Now briskly rub a small quantity of ghee with the index finger or other means on the back of one hand, and note the smell by inhaling. A few drops may also be taken inside the mouth and the taste noted. Determine the acidity (oleic) by the standard method. Finally, examine the package on the inside (after emptying the contents) for cleanliness; and in the case of tin-containers, note the presence of rust, etc.

Requirements of High-Grade Ghee:

Such ghee should have a natural sweet and pleasant odour, an agreeable taste and should be free from rancidity and any other objectionable flavour. A pleasant, nutty, slightly cooked or caramelized aroma is generally prized. A good texture requires large and uniform grains with very little liquid fat; a greasy texture is objectionable. When the ghee is melted, it should be clear, transparent and free from sediment or foreign colouring matter.

The colour should be uniform throughout; it should be bright yellow for cow ghee and white, with or without a yellowish or greenish tint, for buffalo ghee (the intensity of colour depending on the method of preparation). The package should be clean inside and not soiled on the outside if tin containers are being used.

Uses of Ghee:

(a) Major Uses:

(i) As a cooking or frying medium;

(ii) In confectionary;

(iii) For direct consumption (with rice, chapatis, etc.)

(b) Minor Use:

In indigenous pharmaceutical preparations (mainly cow ghee).